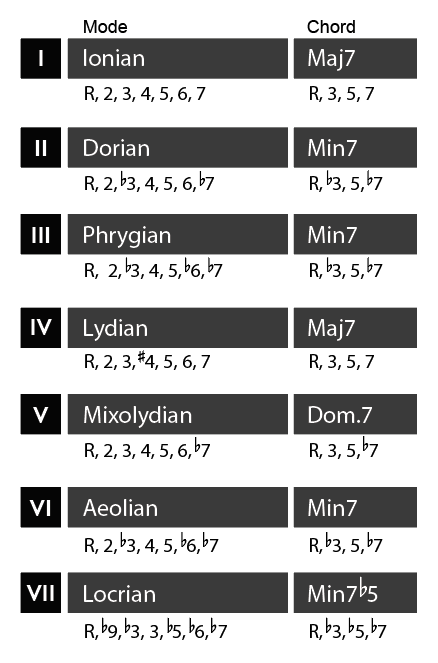

Wes Montgomery's octave solos are perhaps the most distinctive part of his sound, but nearly all of his solos were like a three act play: First, he started with single lines, then he moved to octaves, finally he moved to chords. Just by the sheer number of strings, he was 'building' up his solo.

There are a few different approaches to chord soloing, most of which involve targeting the note on a chord's highest string as the 'Melody Note' with the bottom strings 'fleshing out' what chord is being stated below. The Sixth-to-Diminished approach is a quick-and-dirty chord-scale which you can learn on the cheap.

| six_to_diminished.pdf |

The two-dollar explanation of the sixth-to-diminished is that the chord-scale is continually going from Five-to-One. As outlined in the PDF, the diminished fingering is really an altered Dominant - a Dom.7b9 chord. The ensuing chord is the 'One' chord, the Maj6. Now -- what do jazzers love to do with any harmony? Take any opportunity to add a 'V to I' cadence. The Sixth-to-Diminished has the V to I in spades. Every movement along the chord scale is a V going to a I.

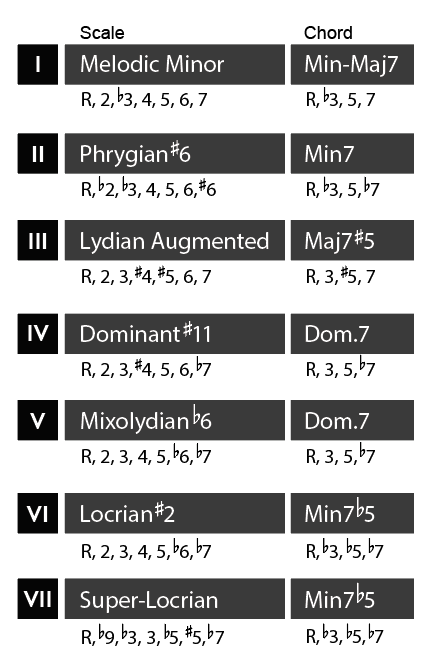

The beauty of the Maj6 chord is you can easily interpret it as Major or Minor. Any Maj6 is an inversion of a min7. You may notice that the diminished chords -- spelled out in the chart as Dom.7b9 -- consistently have a note outside the Diatonic Major scale. The flat-9 of these Dominants are actually the same as a Major#5. I don't have the complete story on the Barry Harris method, but I know the Maj#5 chord is a big part of it.

If you take a look at the Diatonic chords of the Harmonic Minor, you see the Maj#5 is the Third Mode there. If we used the Harmonic Minor's Maj#5 as the 'One' chord, the II mode would be the Harmonic Minor's vi -- Dorian#11. Let's take a look at the Sixth-to-Diminished harmonization of the II in the PDF. It shows a Dom.7b9 to the V, but looking from the perspective of the II, we have the Root, the flat third, the sixth, and the #11. Are the chord tones are outlining the Harmonic Minor starting from the III? Perhaps a discussion for another post.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed