| major_scale_and_diatonic_arpeggios.pdf |

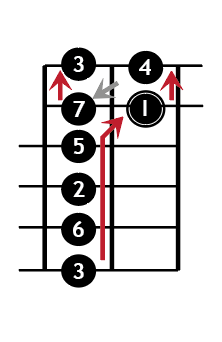

By learning vertical diatonic arpeggios over these chunks -- the vertical scale boxes -- you will begin to learn the layout of the Major scale over the entire fretboard. As you learn the Major Diatonic Chord Progression moving up the neck rooted on the sixth string, these arpeggio shapes can be 'landmarks' of where you are on the neck. From an arpeggio, you can fill in the rest of the notes that make up a particular mode. To have complete fluency, you must understand how to arpeggiate any chord within these seven R6 Mode boxes -- with the chord's root falling on any of the six strings. That is where the third and final section of the pdf comes in -- it shows the arpeggios for each of the seven degrees within each R6 mode box position. For each 'chunk' of the Major scale, you should be able to visualize all the arpeggios in the Diatonic Chord Progression.

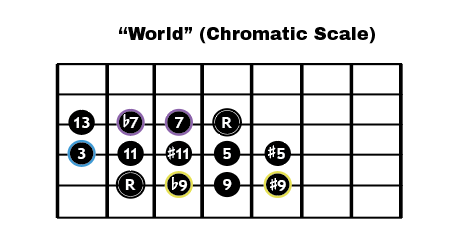

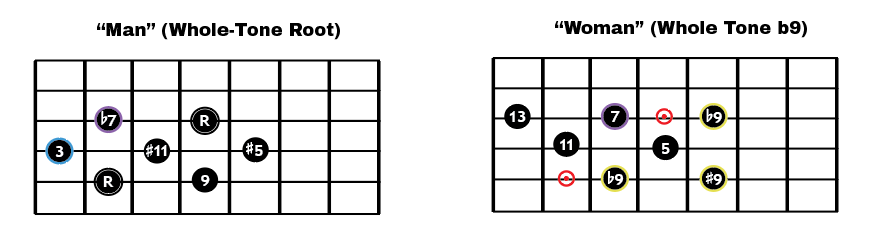

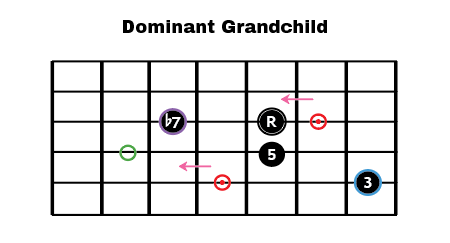

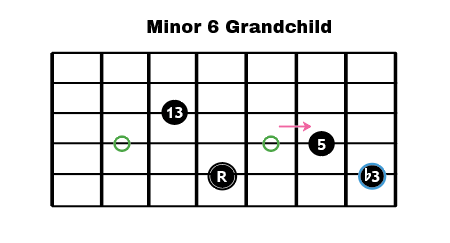

When playing over changes, every nanosecond counts. For each chord in a bar of music, the 'harmonic hierarchy' below is the order in which I visualize the 'best' notes to play:

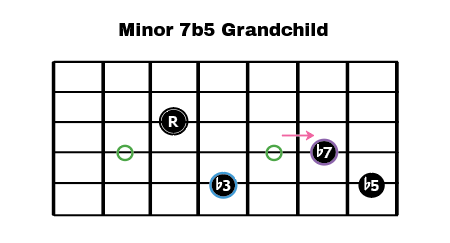

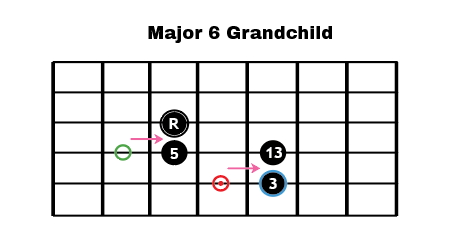

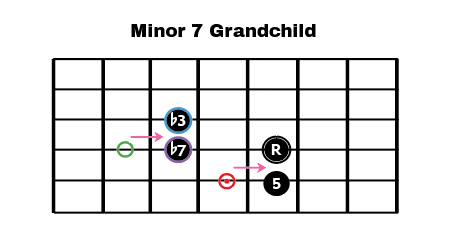

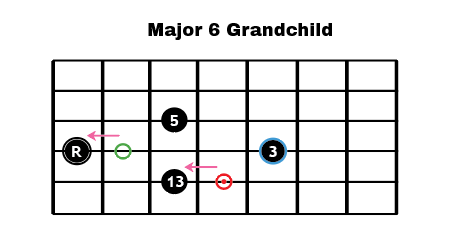

1) the 'essential' chord tones -- third and seventh -- which have a colored outline on the chart

2) the arpeggio of the chord (root, third, fifth, seventh)

3) the chord's mode, or scale tones

An advanced player will also evaluate the harmonic hierarchy of the next chord to the the equation, not to mention arpeggios and scales of substitutions or altered sounds, outside the scope of this chart.

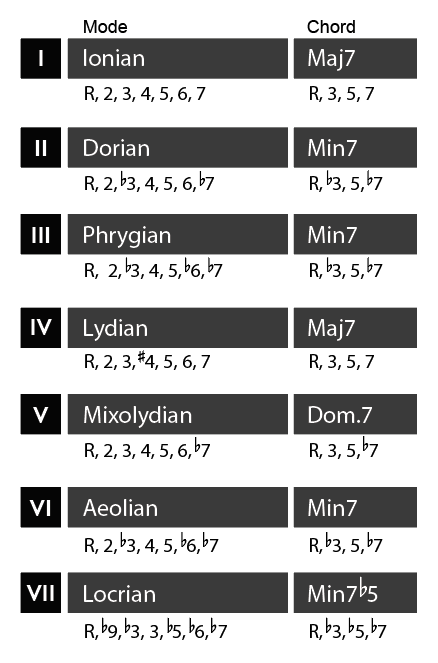

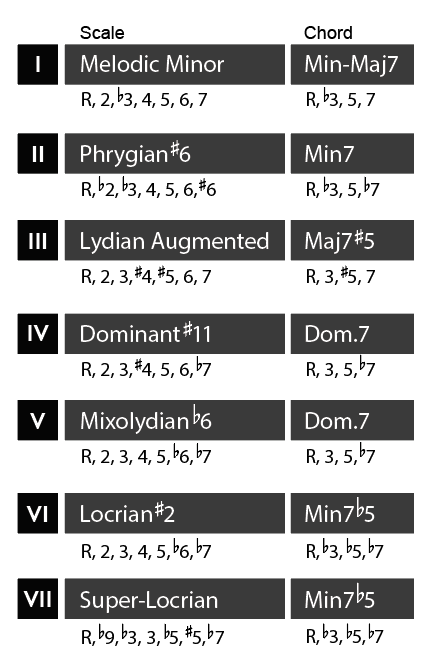

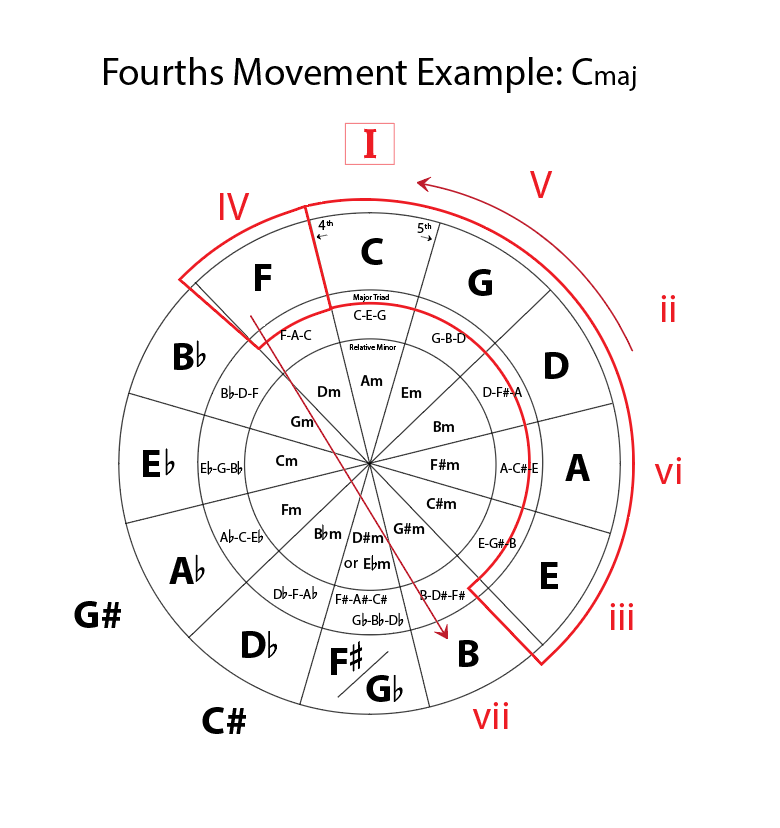

If you shift the root of the scale to a different note of the scale, you will be playing a different mode. As the Major scale has seven notes or degrees, there are seven Modes in the Major scale. The 'Ionian' mode is identical to the Major scale because they have the same Root -- the first note of a scale that sounds like 'home.' When you play the notes of the Major scale starting from the second note, you are playing the Dorian mode. This is the mode for the second degree of the Major scale. The degrees are usually notated as roman numerals. So we associate Dorian with the roman numeral 'II'. While 'II' is common -- it is more correct to use a lower case 'ii' for Dorian, but that will be discussed later. Just know that 'II' or 'ii' refers to 'the Two Chord' in a Diatonic progression.

Moving the root note along each of the degrees of the Major scale gives you each of the seven modes. If you play all seven notes of the Major scale starting from the second note, it 'sounds Dorian.' Eight notes up, you reach a note that sounds like you've completed a circle. If that 'home' tone happens to be the second note of the Major scale -- you are in the Dorian mode of the Major key.

Each degree or Major scale tone (one of the 'dots' on the chart) also has an 'arpeggio' associated with its mode. Arpeggios are a selected group of notes in a scale played sequentially. If the notes of an arpeggio are strummed at once, that is called a chord. Arpeggios and chords have the same notes.

The chords associated with each of the seven degrees of the Major scale are called the 'Major Diatonic Progression':

The arpeggio for the I and the ii in a Major key have a different quality. The 'One' chord has a Major third and a Perfect Seventh -- creating a Major 7th chord. The 'third' scale tone of the 'One' chord is the third 'dot' in the scale (Ionian, in this case) when ascending from the root. The 'seven' is the seventh 'dot' in the scale, the note just before the next octave is reached.

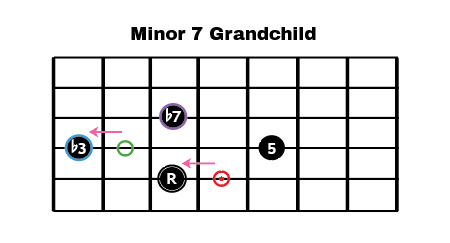

The 'Two' chord in the Major Diatonic Progression is a Minor 7th chord. That is because we are now skipping notes of the mode starting on the II (second note in a major scale now functioning as the root). The distance from dot 'one' to dot 'three' in the Dorian scale is shorter than the distance from 'one' to 'three' for Ionian. With Ionian, the 'third' note of the scale is four frets from the root. However, when you count scale notes (dots) starting on the Root of the Dorian mode/scale, the 'third' note in Dorian is only three frets away from the Dorian root. We say the Dorian's 'third' is 'flatted' one semi-tone , or one fret.

The distance between scale tones (dots) is called an 'interval.' Distance is measured on the guitar in frets. The distance of one fret is a 'semi-tone'. Two frets on the guitar represents a 'whole-tone.' The interval's quality always depends on how the distances line up with the Major scale.

A 'flatted third' is also called a Minor 3rd, because it signals that a chord is Minor. Major thirds (four frets) and flat-thirds (three frets) are both 'intervals.'

All the minor chords in the Major Scale also have 'flatted 7ths.' The 'sevenths' of these Minor chords are one fret (or semi-tone) closer to the root than with a Major chord -- they are 'flatted' from the Perfect 7th of the Ionian Major. The differences of intervals, especially 'thirds' and 'sevenths', are what give chords their quality -- a 'Major' or 'Minor' sound.

There are four qualities of chords in the Major Diatonic Chord Progression:

- Major: Major 3rd, Perfect 7th

- Minor: Minor 3rd, Flat 7th

- Dominant: Major 3rd, Flat 7th

- Half-Diminished (aka Min7b5): Minor 3rd, Flat 5, Flat 7

Even though we have three 'Minor-Seven' chords in the Major Diatonic Progression (plus a Half-diminished -- a minor with a flatted-five), each chord's associated scales are different. This is because at least one of the intervals (fret distances) of scale tones is different in every mode. Every mode in the Major scale has seven notes and seven intervals. Once again, scale tones are black dots and an interval is the fret distance from the root to said dot. Every mode has a 'Root', a 'two', a 'three', a 'four', a 'five', a 'six' and a 'seven'.

To make things slightly more confusing (but 'hipper' for the jazzbo) all the black dots we skipped over to make any Diatonic chord will have an 'alias' called an 'extension.' It is not important to understand extension right now -- that's something that will make more sense when you move beyond the Diatonic chords we are focusing on here. It is useful to learn that the 'two' has a secret 'code-name' -- which is 'nine.' An 'eleven' is code for 'four', and a 'thirteen' is code for 'sixth.' Just be aware that each of these following equations represent the same tone harmonically speaking:

- 2nd = '9'

- 4th = '11'

- 6th ='13'

There are three minor-seven chords plus the minor-seven-flat-five in the Major Diatonic Progression. It is most correct to cite the Roman Numerals for minor modes with lower-case Roman numerals. Therefore, the Diatonic minors are: the ii, the iii, the vi and a special half-diminished minor -- the vii -- which has a flatted fifth. Again -- these roman numerals are all scale degrees counting up along our original Major scale in the Ionian mode.

While the chords of the ii, iii, and vi all have the same intervallic formula (Root, b3, 5, b7), the intervallic formula of the scale for the ii, iii, vi (Dorian, Phrygian, Aeolian) are all different. The differences in the minor modes lay in the notes we happened to skip over making the particular mode's minor chord. For instance, the Phrygian scale has a b9 (remember, 9 is code for 2 -- the second note in the scale).

The point is that while the three minor-seven chords in the Diatonic progression all have the same intervals in their arpeggio (R, b3, 5, b7), the intervals of the scale associated with them are different. Look at the sixth scale tone of Aeolian versus Dorian. If you try and play the Dorian scale over each of the minor chords in a Diatonic progression -- it might sound a little 'off' if the rest of the band is thinking iii chord or vi chord.

If you understand all of the above, you will have an excellent foundation for playing jazz or any type of western music. The Diatonic Chords in a song's given key are what make up the vast majority of popular chord progressions. If a song's chords are all Diatonic chords in a Major key, any note in that key's Major scale are 'safe' notes to play -- all those dots will be 'consonant.' If you are able to play an arpeggio for a given chord when it appears in a chord progression (black dots in the second section of the PDF), those arpeggiated notes will sound extremely 'strong' harmonically. If you orient a line with a chord's mode/scale (e.g. play Dorian over a ii chord), that will also sound very 'harmonic.' Of course, you may well know that jazz stretches 'outside' what is is 'safe' and toys with what is 'harmonic', but I vote for learning how to walk before trying to run.

The goal is for your eyes, ears and fingers to instantly know where all the 'strong' notes (black dots) are when a particular chord is playing. The configuration of these dots should be constantly changing in your mind with each chord. This will take a lot of practice -- probably at least a year for a beginner working incessantly with a teacher and very likely more. I am still finding holes in what I know many years in. But it is possible and it is worth it! Being able to visualize all the Diatonic modes and chords of the Major scale from anywhere on the fretboard is a must for the jazz guitar player.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed